If over the course of the first 3 parts of this series I’ve in any way obscured rather than clarified my thesis, let me here explain it… No, there is too much; let me sum up: I believe—through Scripture, tradition, and reason—that because God is all-Good, all-Knowing, and all-Loving, he, though he allows evil for a time in his Creation, will defeat all evil and save all creatures. He necessarily wants to save all because he loves all, knows how to save all because he knows all, and has the power to save all because he is ‘all-mighty.’ He will do this without violating any rational creature’s free will because free will, by nature, is teleological—always looking for the ultimate Good (who is God)—and will, by God, eventually be liberated from whatever ignorance, error, or pathology that might keep it from recognizing and turning to the loving Maker of all. Again, reason emphatically leads to this conclusion, but Scripture and tradition also support it, though with language ambiguous enough to allow others to reach different conclusions and present objections to this thesis of universal restoration. I now want to address some of those objections head-on.

I wasn’t sure how best to order these objections, so I’m going to address them in a somewhat random order, beginning though with maybe the most obvious and frequent objection:

“Universalism does away with hell.” A properly Christian, and indeed Orthodox, universalism certainly does not disbelieve in “hell” (though we need to make clear here that “hell” is an English term often used in Bible translations and in popular thought to cover Hebrew and Greek terms/concepts like Sheol, Hades, Gehenna, Tartarus, and the Lake of Fire). Orthodox Christian universalism neither denies nor negates the fiery language used in the Scriptures (and especially by our Lord) to describe the judgement, sorrow, regret, or dismay which will be visited upon the wicked after death—either pre- or post-resurrection. It simply disbelieves in the fixity, the finality of hell. It disbelieves in a hell without hope, a punishment without purpose, a reality that ultimately thwarts the inexhaustible love, wisdom, and power of God.

“That basically just turns hell into purgatory.” Well, yes. What’s the objection?

“The bible says that hell is eternal.” See the previous post on Scripture and Tradition. But no, the Bible does not conclusively say either the κόλασιν (chastisement) or the πῦρ (fire) will be interminable, but will rather be αἰώνιον (of the age). The strongest language about duration or finality that might suggest the permanence of anguish is the declaration in Revelation 20:10 that the devil, the beast, and the false prophet will be thrown into fire and “tormented day and night, to the ages of the ages (εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων).” Every other time the phrase “to the ages of the ages” is used in Revelation, it’s used in reference to the glory and praise of God or to the activity and reign of his saints. That phrase has also been picked up by the Church as the primary formula for concluding prayers by declaring (the duration of) the reign of God. The meaning of this phrase is slightly ambiguous since its grammatical construction is so strange. In its literal sense, it basically means “age after age after age, etc,” so it could be interpreted either as an indeterminate succession of ages or epochs, or as eternal and everlasting. Those committed to the belief in an everlasting hell on other grounds will see this phrase as meaning “everlasting,” and those who believe in God’s triumph over hell on other grounds will see this as a rhetorically strong, even hyperbolic usage of an open-ended phrase implying an extremely long duration or an indubitable judgment of God’s. To base either belief on this one instance of this use of this phrase alone, however, would be indefensible. As a side note, the word translated “torment” in most versions of that verse from Revelation comes from βάσανος and has connotations of testing or trying, reinforcing the notion of the λίμνην τοῦ πυρὸς as a refiner’s crucible.

“Universalism means that all paths lead to God.” Orthodox Christian universalism does not argue or imply that all paths lead to God (though there’s no path down which God cannot chase or pursue someone). In a nutshell, it believes that the only path to the Father is by Christ, and that eventually everyone will come to the Father by Christ.

“Universalism was condemned by the Church.” Again, see previous post. The simple affirmation that God will in some way eventually bring all his children to union with himself is never condemned or named as a heresy in any ecumenical council of the Orthodox Church. I would ask those who say otherwise to provide the declaration or canon in which it is. What is the official eschatological dogma of the Orthodox Church? It’s that Jesus “shall come again with glory to judge both the living and the dead; his kingdom shall have no end,” and that we “look for the Resurrection of the dead, and the Life of the world to come. Amen.” That’s it. These are the relevant clauses in the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, compiled and affirmed in its full form at the second ecumenical council.

“Universalism goes against Church Tradition.” Church Tradition, including the holy Scriptures, is multifaceted and dynamic. Of course it has maintained careful continuity and preserved what’s essential (as παράδοσις / traditio basically means “handing on”), but it also—over time and through dialectic interaction between East and West, patriarchate to patriarchate, monastic house to monastic house, culture to culture, and generation to generation—has been developed and refined and renewed. Included both in the Scriptures and in the liturgies of East and West are simultaneously found words and phrases and ideas that suggest the possibility of eternal loss and of ultimate, universal salvation and restoration. Many of the same arguments about words and idioms in the Bible can be applied to the liturgies as well, since they are largely the same (e.g. αἰώνιος). It is true that the majority of writings from the Fathers and divines of the Church ostensibly reflect an eternal hell position, but there are also writings from Saints and Fathers and divines that reflect a total restoration. It’s inaccurate to assert that there is no or vanishingly little universalist language in either the Scriptures, the liturgies, or the Saints. So actually universal restoration is part of the Church’s tradition.

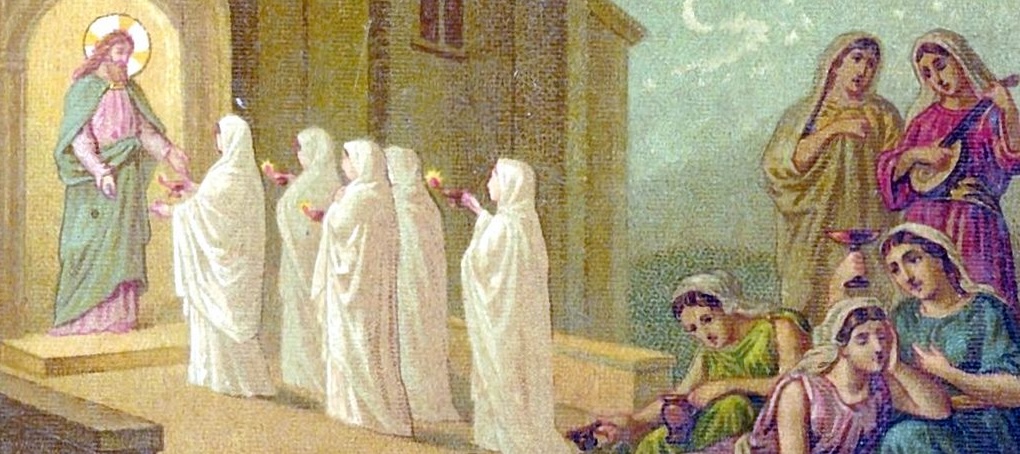

“If we’re all going to be saved eventually, then nothing we do matters here and now.” No advocate of Christian apocatastasis, as far as I’m aware, ever says this. Choices matter, and they have consequences. And the consequences of being grouped with the goats on the day of Judgment (i.e. having not opened one’s heart to God’s grace and acted with charity toward others) will undoubtedly be terrible… just not EVERLASTING. Even if, say, in the parable of the wise and foolish maidens, the five foolish maidens who are unrecognizable in the dark because their lamps aren’t lit are on the morrow belatedly granted entrance to the feast, that doesn’t negate the fearful reality of having to spend a cold, dark, and lonely night in the wilderness, nor diminish the Lord’s warning about it. To use other imagery, the feeling of even one second spent in the unmediated, fiery Presence of the living God with a soul alloyed to sin and selfishness defies imagination, and the pain of that purgation should not be underestimated.

“Universalism denies people’s free will.” See part two of this series. Free will by its nature is not the ability to arbitrarily choose one of multiple options (that’s called randomness), but is teleological, aimed at a good. Any will that would not finally choose the ultimate and objectively highest good, then, is not truly free, but is bound either by ignorance, error, or pathology, or some combination thereof. But God is able to liberate a creature’s free will to choose him by removing any ignorance, correcting any error, and healing any pathology. No fully, completely rational and free creature can recognize the goodness of union with God for what it is and the non-choice of rejecting God and then still make the “choice” to reject God. So universalism, in fact, depends on people’s free will. Now, we may say that this process of salvation may begin “against a creature’s will,” and may go on for some time against its will, in the sense that the creature may not initially want to be educated, corrected, purged, etc. But again, a “will” that fails to recognize and move toward God as the highest good is not free, but bound.

“Universalism denies God’s free will.” Some think that we may hope for the restoration of all but cannot confidently believe in it because that would be presumptuously confining God to a certain course of action, declaring that God must save all. I have to admit that of all the objections to restitutio omnium, I understand and sympathize with this one the least. We all agree that God “desires all people to be saved,” right? Well, that’s God’s will, which is, of course, free. The only obstacle to universal salvation would be creaturely will, not God’s will. And if creaturely will can be healed and liberated by God (as we’ve already seen above is certainly within his power), then all obstacles are removed, and God will do what he desires… which is to save all. I can’t help but think this objection has something else lurking behind it, perhaps for example…

“God’s dignity is infinite, so sinning against him deserves infinite punishment.” God’s perfect justice—it is argued—requires an infinite sentence for the infinitely horrific sin of ignoring, rebelling against, or rejecting God. Even on earth, the more important a person or institution is, the more seriously we punish crimes against them. So if God is of infinite worth, then crimes against God should be punished—it is argued—infinitely. What this reasoning fails to take into account, however, is the degree of culpability (reflecting the capacity) of the criminal. Minors and the mentally ill are treated differently in our justice system than competent adults, and we make an effort to have the sentencing reflect not only the seriousness of the crime but also the culpability of the criminal. At the ontological level, all creatures, whether humans or angels, are finite in our understanding, our competence, our rationality. The obvious corollary to this is that every creature’s culpability in sinning is also finite. Even though God’s worth and dignity are infinite, our culpability is not. So perfect justice would actually accord not only to the relative seriousness of the crime, but also proportionately to the finitude of the creature. Thus, an infinitely enduring sentence for finite sin would be unjust to an infinite degree, as the difference between infinity and any finite amount—no matter how cosmically huge—is still infinite.

“If hell isn’t eternal, then it has no point.” This will be the last objection I’ll look at for now, as I think it kind of sums up all the other objections. I once had an Orthodox priest write to me these very words: “[Universalism] posits a God who subjects his creatures to torture even knowing full-well that it is ultimately unnecessary. … I especially find the idea that God will torture people for aeons until they love Him to be blasphemous and completely against the whole loving character of God.” I let him have the last word in our correspondence because I sensed that nothing I said would shift him from his position, but his (willful?) misunderstandings and/or misrepresentations of the Christian universalism represented anciently by St. Gregory of Nyssa, modernly by Sergius Bulgakov, or contemporarily by Fr. John Behr were staggering. My initial thought in response was, of course, “So torture for eternity is more loving than torture for mere aeons?” But to engage with him further down that line of reasoning would also have been to cede to him his use of the term/concept of “torture.” I know in his conception of eternal hell he doesn’t think of it as God actively or maliciously “torturing” the damned; he holds to a broadly Orthodox view of “hell” (best articulated, I think, by St. Isaac of Nineveh) that hell is just the experience of God’s presence for those who reject him. But so do I! So do many Christian (and especially Orthodox) believers in universal restoration! We just believe that the experience is actually productive for the condemned: to burn the chaff out of their wheat, to bring out the dross from their gold, to liberate them from ignorance or illusion or infirmity, so that they will finally be saved, if only as through fire. This is the way our nature requires us to be saved as rational but finite creatures. Purgation, education, salvation. The answer to this objection is actually just to point out that it’s backwards. If hell is eternal then it has no point, no telos, no goal. But God will always and ever work to bring those he loves (and he loves all) closer into union with him, through the hell of fighting against it, the purgatory of acceptance and repentance and the beginning of cooperation, the various degrees of the slopes of paradise, further up and further in, from glory to glory. Amen.

Pingback: Restitutio Omnium, Part 3: Scripture and Tradition | One World Story