I’m neither a Biblical nor Patristics scholar. I don’t know classical or koine Greek, don’t know Latin, and I’m not well-read-enough even in translated primary sources to claim any expertise. But I have been expanding my knowledge of both the Bible and the Tradition of the Church through amateur study as much as I can. And as my moral and philosophical reasoning over these last 8 to 10 years has increasingly discerned the necessity of a total reconciliation of all rational creatures to their Creator, I have happily learned that, contrary to my long-held indoctrinated position, the Scriptures and Tradition (of which the Scriptures are really a part) not only do not disprove the notion of restitutio omnium, but they amply support it.

Scripture

Let me begin with a broad assertion as a time saving measure instead of slowly building up a case from a multitude of individual passages here: the general sweeping story of the Bible is of God offering blessings and relationship to humans, humans seeking anything other than relationship with their own source of life, God unleashing a death-like sentence on the wicked and rebellious humans, and then God hinting at, promising, or even providing an eventual restoration to the humans from their death-like consequence. The primal example of this is the exile of Adam and Eve from Eden, when their misstep rendered them no longer fit to remain in that paradisal garden. In this foundational and paradigmatic story, exile (symbolically synonymous with death in the Scriptures) is actually carried out as a medicinal measure, to prevent an immortal and everlasting cycle of sin and disobedience! Exile and death, it seems, actually becomes the crucial preliminary path through which life is gained. As Fr. John Behr is fond of pointing out, the pattern in Ps. 104 (103 LXX):29-30—the composition of which may even pre-date that of Genesis— is first of death, then of life/creation: “when you take away their breath, they die and return to their dust. When you send forth your Spirit, they are created…”

I start with this assertion of a pattern because I think this idea, this narrative design, is more important than a string of proof texts. If you want a list of Bible verses indicating or intimating the eventual salvation of all people, there are several readily available (for example, here, here, here, here, and here, to provide just a few lists). The problem with lists like these though, even if they might open the eyes or unlock some closed door in the minds of some to universal salvation, is that there are similar lists which could be compiled to suggest an image of the everlasting damnation or even destruction of some people (for example, here, here, here, here, and here). If you’ve never gone through all of these verses to weigh the comparative merit of each as more favorable to the idea of an everlasting hell vs. the idea of a total reconciliation of all creatures to their Creator, then I’d encourage giving it a go; it’s important to at least have a sense of the cumulative weight of these verses.

But in your deep dive down these lists in English translations of various calibers, bear in mind that the words “eternal” and “everlasting” that you will see time and time again are probably going to be translated from the Hebrew word olam and the Greek word aionios, or some variant thereof. Olam (עוֹלָם) in Hebrew and ainoios (αἰώνιος) in Greek both have a huge range of meanings and semantic usages, including “long duration,” “age-long,” “an aeon/epoch”, and “world/dispensation,” as well as “forever” or “eternity” depending on context. These meanings are often indeterminate and ambiguous. Depending on your translation and the (almost inevitable) theological bias behind it, you can get a vastly different range of English renderings. For example, with Matthew 25:46… “καὶ ἀπελεύσονται οὗτοι εἰς κόλασιν αἰώνιον, οἱ δὲ δίκαιοι εἰς ζωὴν αἰώνιον“:

And these shall go away into everlasting punishment: but the righteous into life eternal. (KJV)

And these shall go away into age-abiding correction, but the righteous, into age-abiding life. (REB)

And these will depart into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life. (RSV)

And these will go to the chastening of that Age, but the just to the life of that Age. (DBHNT)

So you absolutely cannot rely on the words “eternal,” “everlasting,” and “forever” to clearly and indisputably mean “a duration without end” in any given passage in these English translations. That simple trump card is exploded. But a similar treatment could be used for the various Hebrew and Greek words throughout these “proof texts” for what gets rendered in English as “all [people]” and “every [person/creature]”, which is why, in the absence of a simple definitional crutch for a single word here or there, I think it’s much more productive to simply acknowledge the semantic range of all these various terms and to lean instead on the narrative, moral, and theological thrust of the Scriptures.

As Christians, we believe the true hermeneutical key to the Scriptures is Jesus Christ himself, who, only after the completion of his work did he, “beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, interpret to [his disciples] in all the Scriptures the things concerning himself.” St. Paul had been an expert in the Jewish Scriptures as a student under his master Gamaliel, but an encounter with the risen Jesus made him read those Scriptures he knew so well in a completely different way. So if Jesus is the hermeneutical key, we have to discern: who is Jesus? He is the Son and Word of God from all eternity (Jn 17:5), who came into the world as a man to redeem our human nature from death (Jn 3:16), who accomplishes that impossibly mighty task through his own death (Isa 55:11, Jn 19:30) and resurrection (1 Cor 15:20), who becomes the ultimate bringer of cosmic justice (2 Cor 5:10, 2 Tim 4:1), and finally reconciles all things to himself (Col 1:20, 2 Cor 5:19, 1 Cor 15:28). And crucially, all of these accomplishments of Christ are done in and motivated by love (1 Jn 4:7-21).

So in the person of Christ and his work we see extraordinary love accomplishing undreamt-of rescue, life accomplished through death, and justice terminating in reconciliation. It’s Christ who, as the hermeneutical key, reveals the heart of God and illumines the pattern of exile and restoration in the Old Testament Scriptures: Adam and Eve exile themselves and all their progeny from paradisal relationship with God? Well, Mary reverses Eve’s presumption with her assent (Lk 1:38), thereby bringing into the world the new and sinless Adam who recapitulates all of humanity in his own saving Body (1 Cor 15:22). God executes extreme judgment on an extremely wicked generation with a flood? Well, those souls are not abandoned to hopelessness in death but are visited by Christ in his own death (1 Pet 3:19-20, 4:6) and set free from that prison (Eph 4:8-10). Sodom and Gomorrah are destroyed (Gen 19:24-25) with an “eternal” fire (Jude 1:7) and Samaria reduced to rubble because of its sins (Micah 1:6)? Well, even their fortunes get restored (Ezk 16:53). The common tongue of prideful humanity is confused and they are scattered across the earth from Babel (Gen 11:8-9) as multiple nations to be administered by various spiritual principalities (Deut 32:8)? Well, Pentecost reverses Babel when the various nations miraculously hear one tongue (Acts 2:8-11) and the authority of Christ is exercised over those principalities (Matt 28:16-20, Rom 8:38-39).

Over and over again through the Scriptures, a sentence of death and/or exile is pronounced in order to stay the spiraling sin of wicked actors, but then restoration is enacted or promised. In fact, restoration can’t but happen except through the portal of exile and death. For those who believe in and unite their own lives to Jesus’ life, who in fact “die to themselves” (Matt 16:24-25, Gal 2:20), their physical death becomes united with Jesus’ death so that they are raised to Jesus’ new life. For those who are not united with Jesus’ life, their unwilling physical death is not united with Jesus’ self-emptying death, and for them a second death is required: that dying-to-self which is requisite to attaining to the Christ-life. All of humanity is rescued from physical death (Jn 5:28-29, 11:23-24, Matt 22:31-32), but to attain true life in Christ, a willing “death-to-self” must first be accomplished. The question is whether that happens in this earthly age, or in the age to come. The Judgment at this end of this age will tell.

This double horizon, of a Judgment on humans (and angels) at the end of this present age and of a final restoration of all things at the end of that coming age, is articulated and summarized by D.B. Hart better than I can:

“…One set of images marks the furthest limit of the immanent course of history, and the division therein—right at the threshold between this age and the ‘Age to come’ (olamha-ba, in Hebrew)—between those who have surrendered to God’s love and those who have not | And the other set refers to that final horizon of all horizons, ‘beyond all ages,’ where even those who have traveled as far from God as it is possible to go, through every possible self-imposed hell, will at the last find themselves in the home to which they are called from everlasting, their hearts purged of every last residue of hatred and pride. Each horizon is, of course, absolute within its own sphere: one is the final verdict on the totality of human history, the other the final verdict on the eternal purposes of God—just as the judgment of the cross is a verdict upon the violence and cruelty of human order and human history, and Easter the verdict upon creation as conceived in God’s eternal counsels. The eschatological discrimination between heaven and hell is the crucifixion of history, while the final universal restoration of all things is the Easter of creation.“

The most horrible, atrocious, ugly, corrupt, and sinful action ever perpetrated by humanity was the crucifixion of the Son of God made Son of Man. At his crucifixion, as the recapitulation of all mankind, Jesus Christ took onto himself the capitulation of all human sin. And he conquered it by submitting to it: letting it exhaust its finite power on his infinite strength and love. And in the most unexpected, awe-inspiring, life-transforming move never contemplated by anyone before the event, he raised himself up again to a new immortal life and filled human nature with the promise of the same. The death and resurrection of Jesus is the hermeneutical key not only to the Scriptures, but to the cosmos. Death becomes transformed and life becomes (truly) eternal.

Tradition

Not all Christians have perceived the aforementioned double eschatological horizon of a Judgment at the end of this age with the separation of “sheep and goats”, followed by the accomplishment of the secondary death (to self) and restoration of the “goats” in the final reckoning of all things beyond the immediate horizon. Today, the prevailing view instead sees only a single horizon in the eschatological language of the Scriptures. This idea is that at the end of this world, Jesus will Judge all people (and “the devil and his angels,” Matt 25:41), the verdict of which will result in two distinct classes of creatures, one experiencing eternal bliss, and the other a fixed torment perpetuated through all eternity with no hope of learning, reformation, healing, purging, or amendment (this tradition having become ossified as the “four last things” or quattuor novissima: death, judgment, heaven, and hell). The only difference really between the single horizon and the double horizon vision is that in the former the judgment and verdict on the condemned is non-reformative, non-curative, and breaks with the biblical pattern outlined above.

It’s likely that from the very first generation of Christians, both of these eschatological ideas were held (as well as the annihilationist variant on the single horizon view, where instead of interminable agony, condemned creatures are rather wiped from existence after the Judgment). Despite the claims by some that the universal reconciliation position was always an extreme minority or fringe theory, there is thorough scholarship demonstrating that not only was the idea of restitutio omnium (or apokatastasis in Greek) held by many if not most people in certain times and places in the early Church, but that there were many Saints and Fathers of the Church who held either a confident or hopeful version of this doctrine (see, for example, Christ Triumphant by Thomas Allin and especially A Larger Hope? by Ilaria Ramelli).

One of the most notable of these great teachers of the early Church was Origen of Alexandria (c. AD 185 – c. 235). Origen was the most prolific and influential biblical scholar and theologian of his day, and also the most noted expounder of the doctrine of universal reconciliation. But famously he was, in an extremely irregular manner, posthumously condemned at an Ecumenical council in 553 (or was he?), over 300 years after his death in good standing as a confessor of the Church. The timeline and causes of the besmirching of Origin’s reputation and his eventual denunciation by name in the canons of the 5th Ecumenical Council has been brilliantly and thoroughly covered in an article by Fr. Al Kimel here. The short version is that in the centuries after Origen’s death, some monastic groups in Palestine claiming to follow Origen’s teachings actually distorted or exaggerated some of his writings and began espousing wildly esoteric metaphysical systems (involving a realm of pre-embodied souls which all fell to varying degrees and became either angels or humans or demons, among other ideas) which of course fell far afield of any traditional Jewish or Christian teachings. Because of the extravagant errors of those who claimed to follow and represent Origen’s thought, the great man himself was anathematized either at or at least in the later records of this Council, though no actual reasons were given for Origen’s condemnation; those reasons were only explicated in lists of anathemas compiled and ratified outside of any ecumenical ecclesial context. Among the various doctrinal ideas (erringly) ascribed to Origen and condemned in these lists was the “monstrous restoration” which followed by reason of some metaphysical necessity from an original unity of all things before a pre-cosmic fall. Crucially, what is never condemned either in these lists or in any Ecumenical Council is the notion of universal salvation following the standard Christian understanding of creation, fall, and judgment.

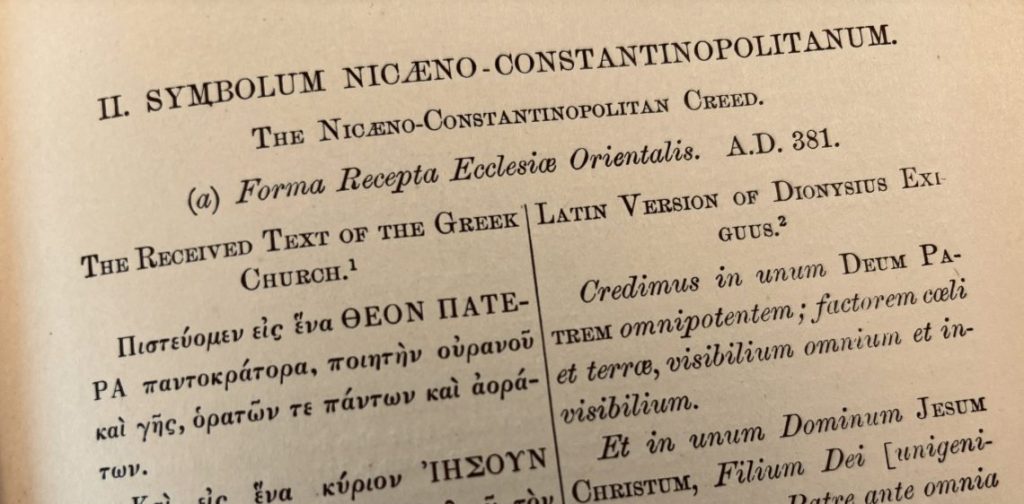

If such a view had been condemned, then one of the most important Saints of the early Church would almost certainly have had to have been condemned with it. St. Gregory of Nyssa (c. AD 335 – c. 394) was the very model of Orthodoxy, helping to oversee the completion of the very standard of Orthodoxy—the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed—at the 2nd Ecumenical Council. St. Gregory, one of the three “Cappadocian Fathers,” all of whom it could be argued were either decided or hopeful universalists, was certainly the most committed and overt believer in universal reconciliation. Aiding the presiding Bishop of the 2nd Ecumenical Council, his friend and fellow Cappadocian St. Gregory Nazianzus, Gregory Nyssan (later lauded as “the father of fathers” by the 7th Ecumenical Council) oversaw the the completion of the Church’s official Creed, the symbol of its faith (Σύμβολο της Πίστεως / symbolum fidei), which names the most essential, crucial, foundational dogmas of the Christian faith. Among these are: the judgment of “the living and the dead”, “the resurrection of the dead,” and “the life of the world to come.” Noticeably absent from this list of crucial eschatological dogmas is “everlasting perdition.”

You would think if an agonizing state of hopeless, never-ending torment for a part of humanity and angels was assumed as basic and essential Orthodoxy in the early Church then that would have merited a mention in either the early formulations or final draft of the most important confession of faith the Church ever produced. You would think the worst imaginable “or else” as a counterpoint to belonging to God and his Kingdom would have been articulated in that Creed. You would think the Creed would have presented a future more akin to the later quattuor novissima shape of “death, judgment, heaven, and hell.” You would think. But maybe the Creed never mentions an eternal hell because it wasn’t meant as an evangelistic tool; only Christians would have been reciting it, and they would only have been “looking for” the life of the world to come, not the punishment of the world to come. Or, maybe the Creed never mentions hell because its nature and duration were points of non-agreement (adiaphora) among the bishops of those Councils, and an aside from the really important doctrinal points of the Trinity and the Incarnation. Whatever the case, Christ coming to judge the living and the dead and the universal resurrection are all that’s articulated, the only consequence of which being mentioned is the life of the world to come.

In subsequent decades and centuries, various figures in the Church would make mention of those holding to the notion of total reconciliation, like St. Augustine and his “cordial” disagreements with those “tender-hearted (misericordes)” Christians. By the time of the Emperor Justinian and the 5th Ecumenical Council, the temperature toward this doctrine among the powerful and influential seems to have drastically cooled. The trail of the doctrine of universal salvation seems, at least in the popular telling of the tale, to go cold after Origen’s nominal condemnation in the 6th century—though, again, Ramelli’s ‘A Larger Hope?‘ traces a string of influential Christian thinkers through the medieval period who espoused total restoration.

It’s clear that, for the last 1,000+ years, everlasting perdition became and remained the majority view of the churches east and west, Orthodox, Roman Catholic, or Protestant. This ought to trouble any faithful Christians who firmly believe in God’s ability to restore every one of his creatures to loving relationship with him, not only because they have to come to terms with the vast majority of their own brothers and sisters believing such a hideous doctrine as the eternal agony of some or many of their own human race, but also because they oughtn’t ever to like finding themselves outside of the mainstream of belief in their own communions. But, majority opinion is no guarantee of truth, as Sts. Athanasius and Maximus could attest. And given restitutio omnium is a doctrine held by some of the earliest, some of the holiest, and some of the most brilliant luminaries in Church history, on top of the demonstrable fact that it has never been condemned by an Ecumenical Council (as the Orthodox count them), to hold this doctrine is neither innovative nor heretical. I would also add that the evident and gross misunderstandings of an Orthodox apokatastasis by those who object to it fills me with even greater confidence that this doctrine is, once understood, unobjectionable, irrefutable, and morally, aesthetically, theologically, and rationally superior to any other vision. In the next part, I’ll look at objections to restitutio omnium that I’ve encountered and do my best to answer them with clarity and charity.

Pingback: Restitutio Omnium, Part 2: The Freeing of Free Will | One World Story

Pingback: Restitutio Omnium, Part 4: But What About… | One World Story